This article was published after the 2010 elections. It points to basic characteristics of the relation between Turkey and the Turkish Cypriots.

The explicit or symbolic favour of the United Nations, the European Union, the United States and other western governments, as well as that of Ankara, to Mehmet Ali Talat’s re-election to the leadership of the Turkish Cypriots, in 2010, proved ineffective; veteran politician Derviş Eroğlu continued his 2008 triumphant return to the political scene, winning the election in the first round. Beyond ethical questions, external support in disregard of the will of the voters has also shown the extent to which the international community generally ignored or misunderstood vote and choice processes. In the particular case, the negative symbolic value and the boomerang effect of external support or ‘foreign interference’ might have heavily outweighed benefit, if any. More importantly, Ankara’s failure to influence the outcome showed that views about the kind and extent of her command on northern Cyprus are often surrounded by myths. This applies also to perceptions about positions and the role of different groups of voters.

Failure of external support to Talat and inefficiency of his campaign can only be understood if seen in a long-term perspective, and be connected with both the context and his policies and action. The hopes invested in 2004 and 2005 in the Republican Turkish Party (Cumhuriyetçi Türk Partisi –CTP) and Talat himself ignored three crucial factors:

- In general, following the softening of the dividing line (April 2003), the rejection by Greek Cypriots of the Annan Plan (April 2004) and the subsequent accession to the European Union, was not favourable for pro-solution efforts. In particular, the momentum created by massive Turkish Cypriot mobilisation in 2002 and 2003 and expectations thereof were replaced by a (new) negative climate and revival of feelings of distrust or bitterness between the two communities; thus, hopes had already fainted and the aspirations of large parts of people shifted towards silent or open acceptance of the de facto division;

- The power of the new leader to respond effectively to the hopes of the pro-solution and pro-European Union forces, which had already lost much of their strength and aspiration, was questionable for more than one reasons. As a community, and no more a party leader he failed to respond to the expectations of his supporting groups, which partly alienated them;

- Ankara’s power on the new leader could be more effective than before, since the latter lacked the connections with the Deep State and the potential of his predecessor Rauf Denktaş to defy the Turkish Government’s guidance. This limited more Talat’s manoeuvre margin and increased the distance between his policies and the aspirations of those that had invested in him. Stressed relations with the Greek Cypriots during that period benefited an even stronger influence of Ankara.

All the above, along with the policies followed by Mehmet Ali Talat in economy and other sectors, blamed as too partisan and in some cases as arbitrary, had their impact on the voters; the effects were long-term and structural, they could not be easily reversed. Christofias’ election in 2008 came rather too late and the long course of negotiations engaged by the too leaders could not revert the course of developments. How did the above and other factors reflect on choices and behaviour of different groups?

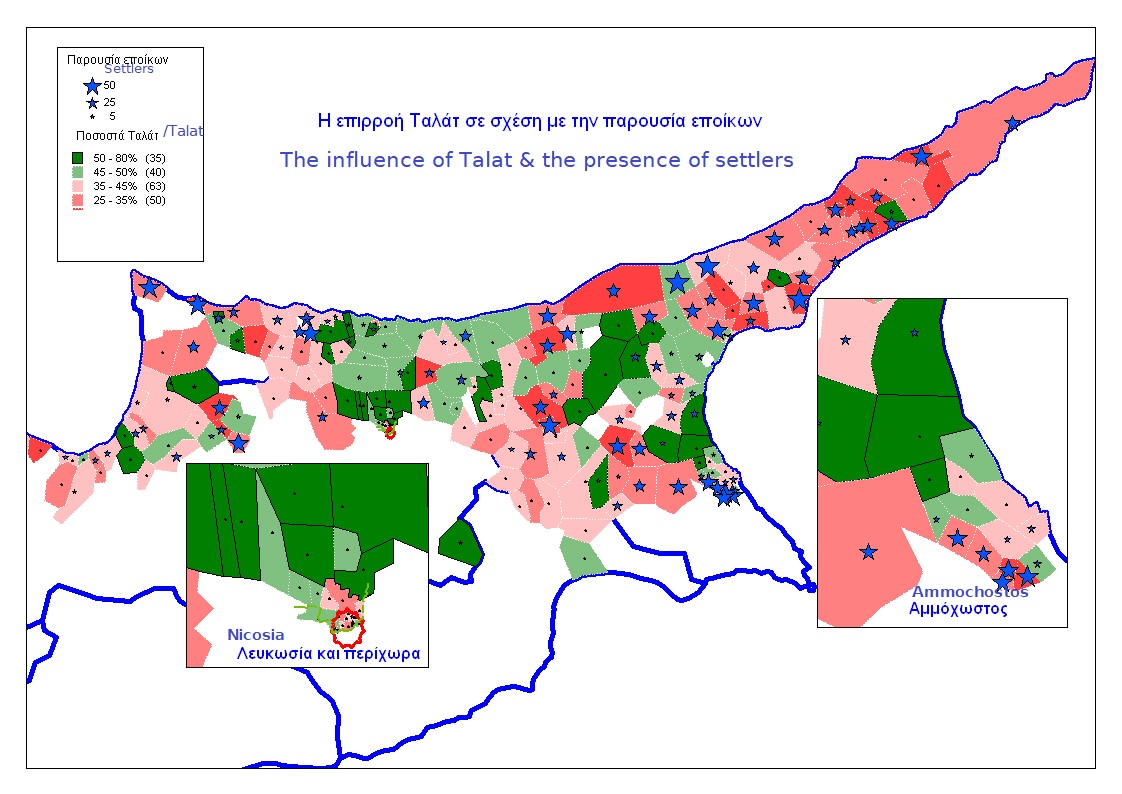

Despite the general view among Greek Cypriots that Eroğlu’s win was due to massive vote by settlers from Turkey, the results show that he won the majority among all groups. Only the town of Nicosia and suburbs gave Talat the lead but not the majority. This is the area where most Denktaş’s supporters shifted in 2003 their vote to become the most dynamic pro-solution and change group.

Interestingly also, traditional Turkish Cypriot communities, that had had little or no contact with Greek Cypriots appear almost equally divided between the two candidates, while those displaced from the south in 1974 deserted Talat in larger numbers, giving Eroğlu 50% (Talat 44%). Their 2004-05 overwhelming support for a solution in spite of the fact that they were to change again residence in case of a settlement has evaporated; they might have been disappointed by developments or their aspirations changed in the new post-2003-2004 context of no solution.

Thus, Turkish Cypriots reverted in bigger numbers to Eroğlu, while settlers continuing their crushing support to conservative candidates gave him 64%.

The new element is that Talat’s share in 2005 and 2010 (32%, 27.6%) shows a breakthrough in this group, from which left wing parties and candidates could hardly get more than 15%. This change might be partly due to the exercise of power by CTP and Talat. However, while the critical mass of settlers vote can decide close to call contests in favour of conservatives, the vote break-down over the years does not justify claims that National Unity Party’s (Ulusal Birlik Partisi -UBP) or Denktaş’s / Eroğlu’s superiority rely exclusively on them. They have been almost consistently voted by the majority of Turkish Cypriots as well.

Similarly, the failure of predictions that Ankara’s influence could revert the trend in favour of Talat raises a more specific question about Turkey’s power and role in north Cyprus. While cases of corruption, influences by military or others have been recorded in the past, there is again an exaggeration about the potential of such practices. Turkey’s role and influence can be decisive on higher levels of politics, not on that of groups or society. For example, there are questions related to the fact that UBP’s history is one of continuous dissensions and splits, affecting its ambitions to dominate politics. Other phenomena such as the collapse of coalitions following Ankara’s interference, such as in 2001, or the delay of funds transfer to feed the budget show the various forms of measures that can influence politics in this part of the island.

The ultimate question, which is relevant also to Eroğlu’s policies, is, to what extent can one expect decisions that deviate from Turkey’s will? Given the total security dependence on the Turkish Army and budget large dependence on funds from Ankara, the only possible alternative for any Turkish Cypriot leader could be to rely on society forces. How strong, though, can these forces be if the voters are largely divided into two camps and large parts are disillusioned about prospects for a better future?