For three years, the government (former and present) has been promoting a bill to amend the Criminal Code, Chapter 154, aimed at criminalizing fake news and forms of electronic communication, telephone and Internet.

The Anastasiades government initiated the bill with its then minister of Justice Emily Yiolitis. There is no point in going into details and the logic of arguments put forward about the exact content, the goals and, above all, the pretentious arguments they had put forward to support the bill. Suffice it to point out that the effort made to found their proposed provisions in Law and Jurisprudence was minimal or negligible.

I would like to state at the outset that this analysis refers to the original bill introduced in 2021, which is the only one that is publicly available.

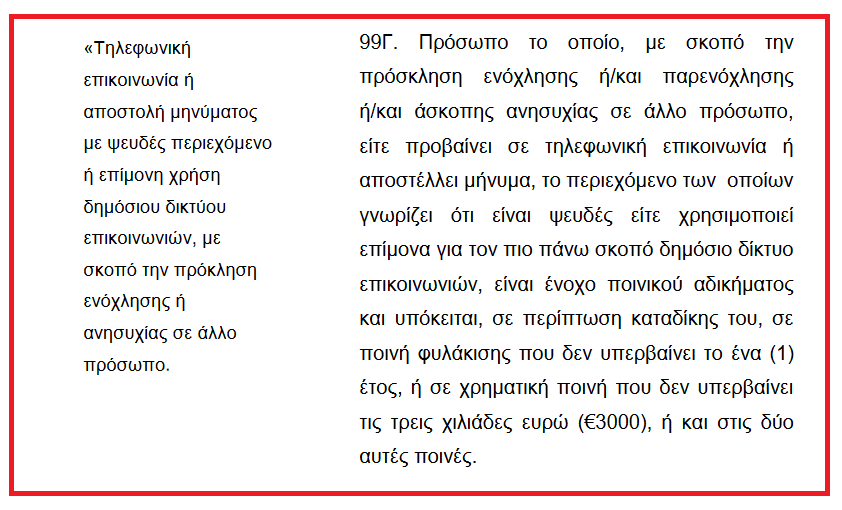

What does the bill provide for? Let’s look at the first section (Article 99C), about false messages:

This section,

- Criminalizes (makes it a criminal offence) communication content which is false.

- Criminalizes “persistent” face-to-face messaging over the Internet.

- Targets interpersonal communication (telephone, internet) and public communication (Internet).

- Criminalizes communication that causes annoyance, harassment, unnecessary worry “to another person”, based therefore on the receiver’s perception (?) of the communication’s impact.

- Provides for prison sentences of up to one year and/or a fine of up to 3000 euros.

In the second section (Article 99D), the bill does the following:

- Criminalizes (makes it a criminal offence) communication content based on its perceived characteristics.

- Targets interpersonal communication (telephone, internet) and public communication (internet).

- Criminalizes communication based on the perception of the character of its content, as grossly offensive, indecent, obscene or threatening a person.

- Provides prison terms of up to two years and/or a fine of up to 3000 euros.

The third and last provision (article 99E),

- Criminalizes (here it is referred only as “an offence”) communication content based on its perceived characteristics.

- Introduces the term “intentional” action.

- Criminalizes communication based on the perception of the character of its content as grossly offensive, indecent, obscene or threatening a person, adding also “abusive /insulting”.

- Provides prison terms of up to three years and/or a fine of up to 5000 euros.

The provisions of the bill, the Constitution and European Law

The judgment and evaluation of the bill must be done in its entirety, but also in its individual provisions as listed in the previous paragraphs. The first issue is about criminalization of false communication content.

Fake content

In Article 19 of the Constitution on freedom of expression, the terms used are ‘opinion’, ‘information and ideas’. Also, in article 50.1 of the Criminal Code Chap. 154 we have the terms ‘False news and information’. In the present case, the reference to ‘fake content’ is not sufficiently definitive as to what exactly it means and what part of the content we will look at to identify the ‘fake’.

In fact, the important issue here is the criminalization of communication content by using the criterion of ‘falsity’. That is, the right to freedom of expression is limited on the basis of this characterization alone. Can this restriction be allowed based on the Constitution and case law?

For an answer, we contend ourselves with an interpretive decision of the Supreme Court in the case of POLICE v. EKDOTIKI ETERIA “INOMENI DIMOSIOGRAPHI DIAS LTD.,” AND ANOTHER, (1982) 2 CLR 63, 29 March 1982 (Question of Law Reserved No. 187), in which the following is stated:

“Held, (1) that the right safeguarded by Article 19(1)(2) of the Constitution is not limited by reference to the truth or falsity of a statement made in the exercise of such right; therefore, it extends to false as well as to true statements.”

It is clear in this decision that the attribute “false” alone is not sufficient enough to criminalize expression and limit the right to free expression. The violation of the right of freedom of expression and the conflict of the provision of the bill with the Constitution are clear.

Reasons for criminalization

The grounds for criminalization introduced by the bill are linked to perception, the feelings that the communication may cause to the recipient, i.e. annoyance, harassment, unnecessary worry. There is no indication or suggestion as to whether and which rights of the person are being violated. Protection from annoyance, harassment or undue worry is not a right in itself or a sufficient justification for restricting freedom of expression, a right which, based on international law and jurisprudence, should receive a privileged treatment when compared with other rights. Even more so in the present case where no right is mentioned in the bill. In the second provision, in article 99D, reasons that constitute a criminal offense are linked to the perception of the nature of the message, i.e. grossly offensive, abusive, threatening, indecent, obscene against a person. In this provision too there is a gap or insufficient justification for the limitation of freedom of expression since it is not defined exactly which rights are protected by the restriction. There are also questions as to why the action here is referred to as an ‘offense’ where in the previous articles it is a “criminal offence”?

Is the offense criminal or a civil wrong one?

Serious questions are raised on why (supposed) offenses of an interpersonal character are introduced into the criminal code, even though they may take place in public space, while, also, their nature does not justify this characterization, and they may simply be reduced to personal disputes.

A more serious element, critically linked to the characterization ‘criminal’, is the manner in which the prosecuting authorities may intervene. With criminalization, the door is wide open to authorities to invade homes, offices, mass media premises with the already known results: Arrests for questioning, criminal law charges, confiscation of communication devices and computers, actions that are outside the Rule of Law and clash with European principles and ECtHR jurisprudence. We note that there are decisions of the Cypriot judiciary too in which the confiscation was characterized as an excessive measure and a violation of the principle of proportionality. The authorities do not have protocols for handling the matter as required by the ECtHR and the Rule of Law.

It is important to mention that, since 2003, the Republic of Cyprus is among the few European countries that have decriminalized libel/defamation, which is a serious offense against the dignity and reputation of individuals. If this issue was changed then from a criminal offence to a civil wrong, what are the serious reasons and what degree of proportionality could allow the criminalization of acts of expression that do not have the weight required for criminalization? No sufficient justification exists for this change.

Freedom of expression and permitted limitations of the right

I will not expand on other issues on the content of the bill, in order to focus on the essence, namely restrictions and the violation of the right of freedom of expression introduced by it. Article 19 of the Cyprus Constitution, as well as Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights, allow the restriction of freedom of expression for the sake of a superior right or interest. Any superiority is decided on a case-by-case basis by the Court. Restrictions may be made, among other, for the security of the state, maintenance of the public order, protection of the public health and public morals, protection of the reputation and rights of others and for the prestige and impartiality of the judiciary.

It has already been indicated that the punishment of false content is clearly unconstitutional, because true or false in itself is not a criterion for restricting free expression.

Annoyance, harassment or causing unnecessary worry to a person are mentioned in section 99D as causes that lead to the restriction of freedom of expression by criminalizing communication content. These issues are not mentioned anywhere in the Constitution or in international conventions and European law as elements that can be invoked to limit free expression. Clearly, this provision cancels the essence of the right to free expression, violating both the Cyprus Constitution and European principles and ECtHR caselaw. It is reminded that as early as 1972, in the case Handyside v. United Kingdom, the ECtHR defined that “Article 10 (art. 10-2) is applicable not only to “information” or “ideas” that are favourably received or regarded as inoffensive or as a matter of indifference, but also to those that offend, shock or disturb the State or any sector of the population“. In the face of this fundamental principle on the right to free speech, how is it possible to consider annoyance, harassment, unnecessary worry, offence, insulting a person as elements that have the power to cancel everybody’s right to free speech?

The provisions of the bill are completely outside the Law, are not respecting basic principles of Law and do not justify any further discussion. The bill cannot be improved since it is completely in conflict / clearly violates the right of freedom of expression.

Any limitation of freedom of expression must meet basic conditions, as already defined in international conventions and in the Constitution of Cyprus. There are three conditions that must concur:

The requirements for any limitation of free expression are as follows,

- To serve a superior right as defined in the relevant paragraph of article 10 of the European Convention of Human Rights and in article 19 of the Constitution of Cyprus. Whether that right actually prevails is judged on a case-by-case basis, with the right to freedom of expression receiving preferential treatment.

- To define the limitation and goals served clearly and precisely in the Law.

- The restriction must be necessary in a democratic society.

From what is presented here, the conclusion is clear; none of the three conditions is satisfied, while the bill creates a perilous danger by restricting freedom of expression and freedom of the press, with negative implications for Democracy. This cannot be accepted or tolerated in a European Union member State.

In conclusion, we note the following:

Freedom of expression is a guaranteed right for everyone, it is a universal right. Freedom of the Media is a vested right founded on this universal right AND it confers special rights and privileges to the media precisely because of their role in society. Any attack on the universal right leads to the erosion of the Freedom of the Media. It is therefore of a critical importance to respect the universal right, not to separate it from the freedom of the media. If the foundation of the universal right weakens, freedom of the media is shaken.

Article published in Kathimerini & Politis on 1 August 2024